Nikola Tesla

Tesla’s Career in Early Electricity Development

In 1882, Nikola Tesla joined the Paris-based European subsidiary of Thomas Edison’s company. His work there focused mostly on the installation of lighting systems in the suburbs of Paris. When management took notice of his skills in electrical engineering and physics, they began to send him on higher level troubleshooting projects in other areas of France and Germany where the Edison company was setting up utilities. During this period, Tesla was offered the opportunity to work on projects making improvements to existing dynamos and generators.

In 1884, one of the managers with Edison’s Paris division, Charles Batchelor, was relocated back to the company’s New York office and he recommended that Tesla be brought on to the Manhattan location. This is how it came to be that on June 6, 1884, Nikola Tesla arrived in America with nothing more than four cents, a notebook of his favourite poems and a reference letter from his former employer. The letter read, “My dear Edison: I know two great men and you are one of them. The other is this young man!” Tesla went straight to Edison’s office and was hired on the spot as an electrical engineer. In his autobiography, Tesla recalled: “The meeting with Edison was a memorable event in my life. I was amazed at this wonderful man who, without early advantages and scientific training, had accomplished so much.”

However, despite these promising beginnings, Tesla left Edison’s company after only a short six months. In modern terms, his role was potentially like that of a junior field engineer, and he would have been one of a couple dozen working out of the Edison Machine Works office in Manhattan. Tesla was tasked with several projects while he was with the company, all of which he was able to work on successfully. In his autobiography, Tesla notes that the manager had promised him fifty thousand dollars. However, he wrote in his autobiography, “it turned out to be a practical joke.” This led Tesla to resign from the company.

When questioned about this misunderstanding, Edison simply replied that Tesla did not understand “American humour.” Nikola’s diary from that period, covering early December 1884 to early January 1885, simply has a large note stretched across two pages that reads “goodbye to the Edison Machine Works.” Tesla was now free to pursue his own work on alternating current machinery.

Over 1885 and 1886, Tesla briefly ventured into running a company under his own name, securing patents for an arc lighting manufacturing and utility company using improved direct current dynamos. Unfortunately, he sold his interests in the company for stock and lost control of the original patents. The entire adventure ended up being a loss for him in a brief setback. Tesla was soon able to connect with new investors and the first patent for the newly incorporated Tesla Electric Company’s AC induction motor was filed in April 1887.

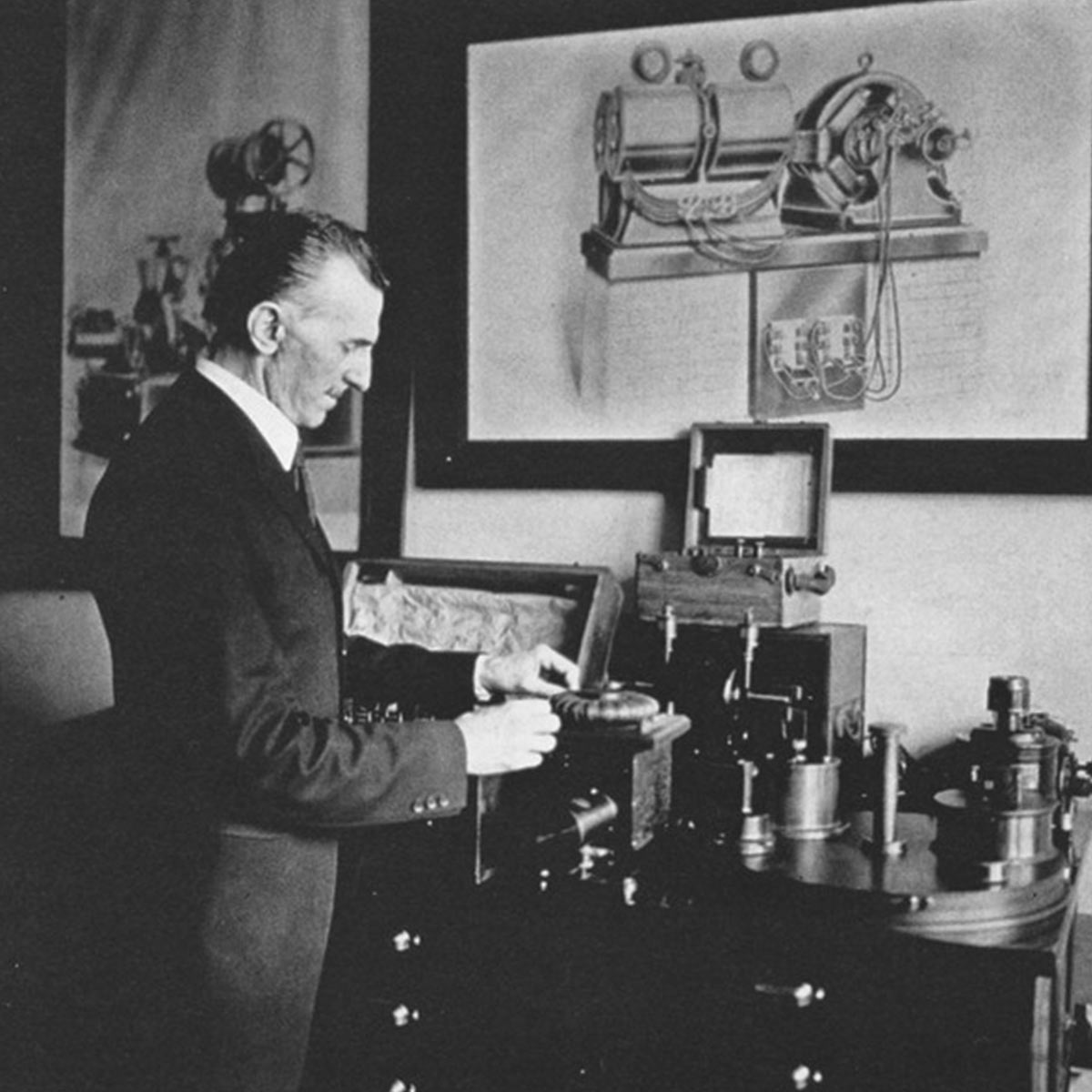

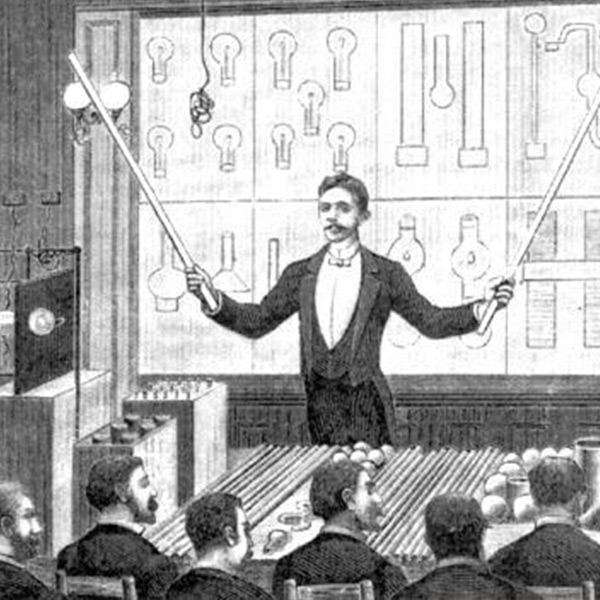

Tesla’s true work on high-frequency alternators began in earnest in 1888. He saw two problems that he wanted to solve: being able to run induction motors at extremely high speeds and then adapting them to the existing alternating circuit supply. In 1889, Tesla designed the first high-frequency machine, and in 1891 he exhibited his first high-frequency alternator.