War of the Currents

Two opposing ideas

Thomas Edison’s General Electric Company was largely unrivalled in North America prior to the War of the Currents. He had long been working on developing practical applications of direct current as he was convinced that it was a better and safer way to power cities. In 1879, Edison invented the first electric light bulb powered by direct current.

In 1886, George Westinghouse created the Westinghouse Electric Company and developed his own brand of light bulbs. After purchasing the rights to Nikola Tesla’s complete alternating current system in 1888, the pair began to work together to advance the concept. Edison found their work to be offensively competitive and decided to campaign against his new rivals.

By 1888, Edison launched a full-fledged propaganda war against the Westinghouse Electric Company to scare the public into believing that its proposed alternating current system was dangerous and unsafe. Some of his tactics included spreading misinformation, publicly electrocuting animals and dubbing the world’s first electric chair execution as ‘Westinghousing.’ It appeared as though Edison’s sabotaging efforts were successful in swaying the public opinion in favour of direct current. That changed, however, at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

Chicago World’s Fair

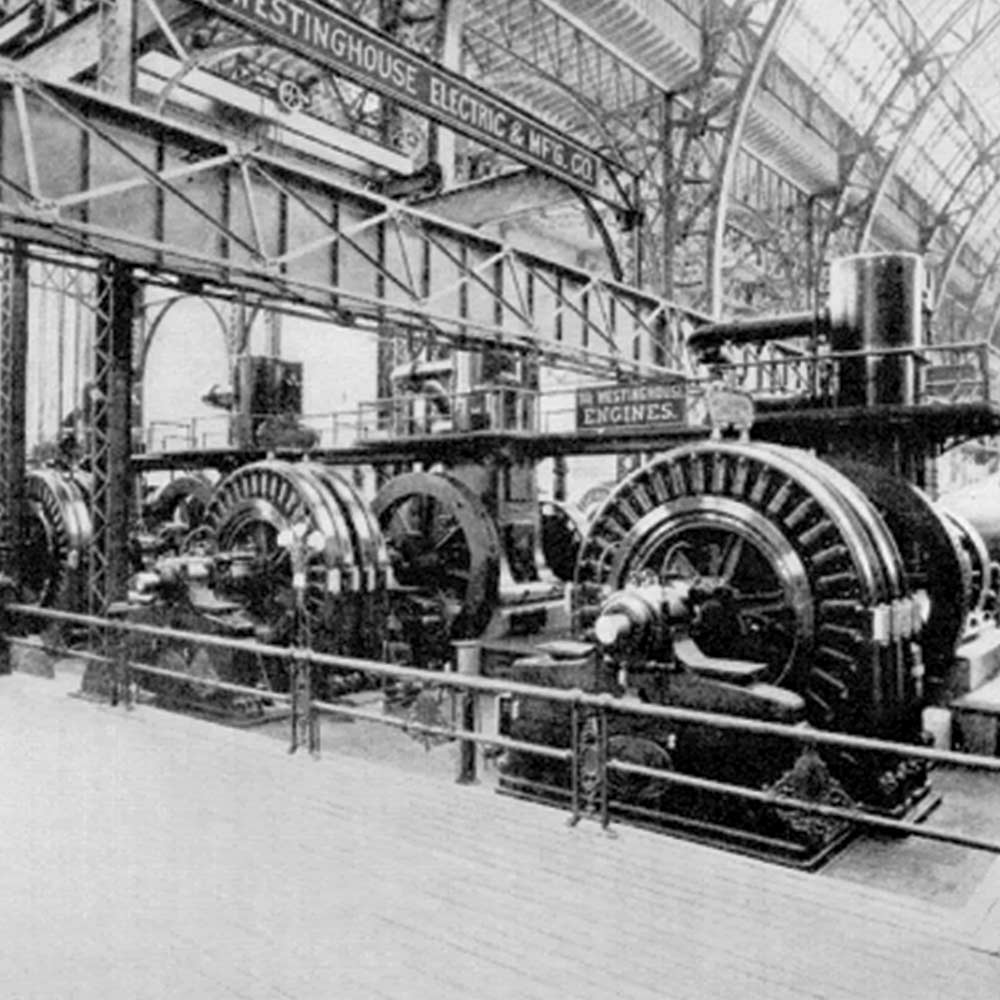

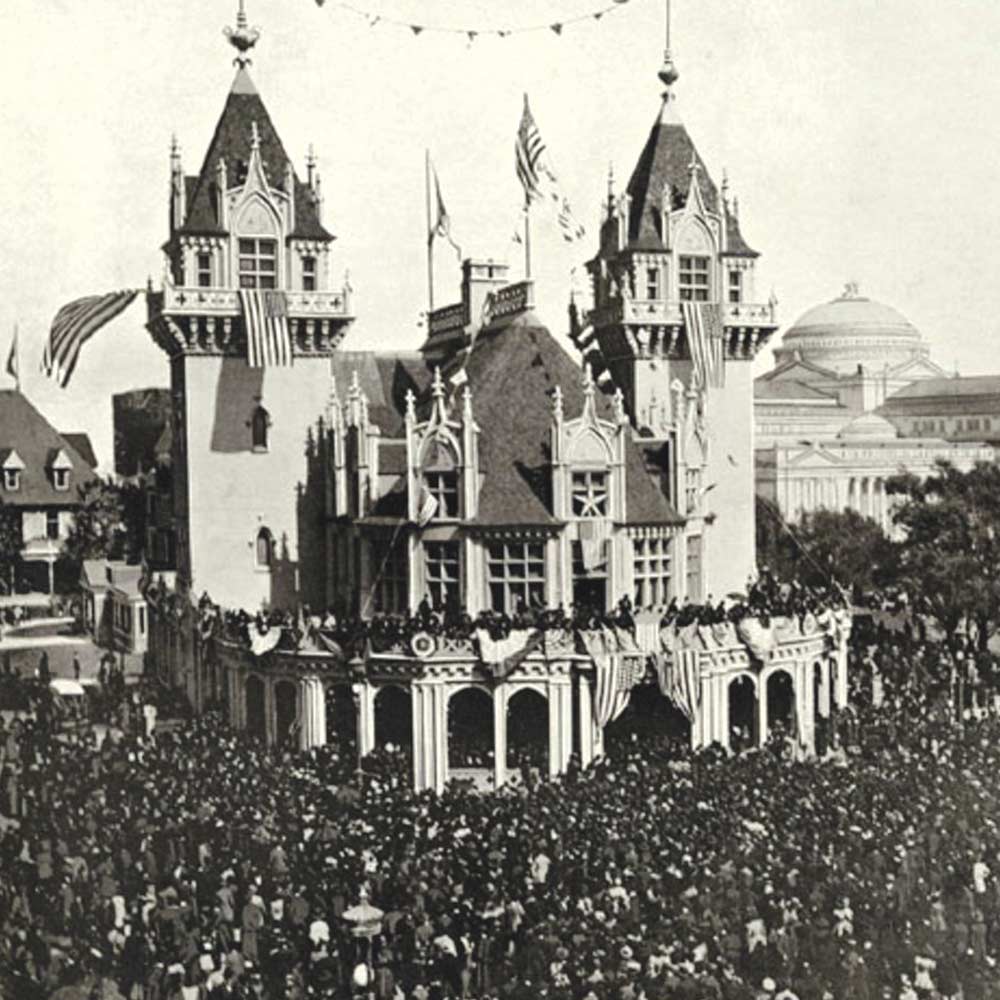

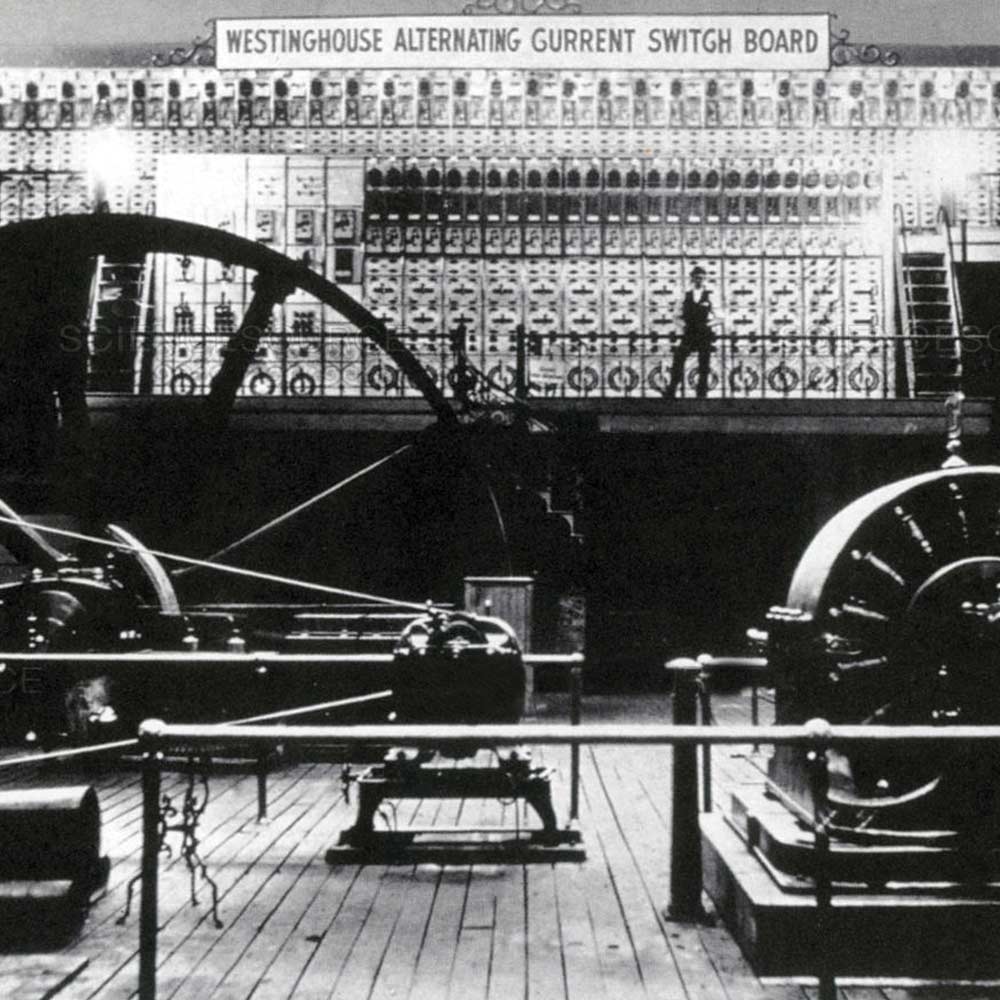

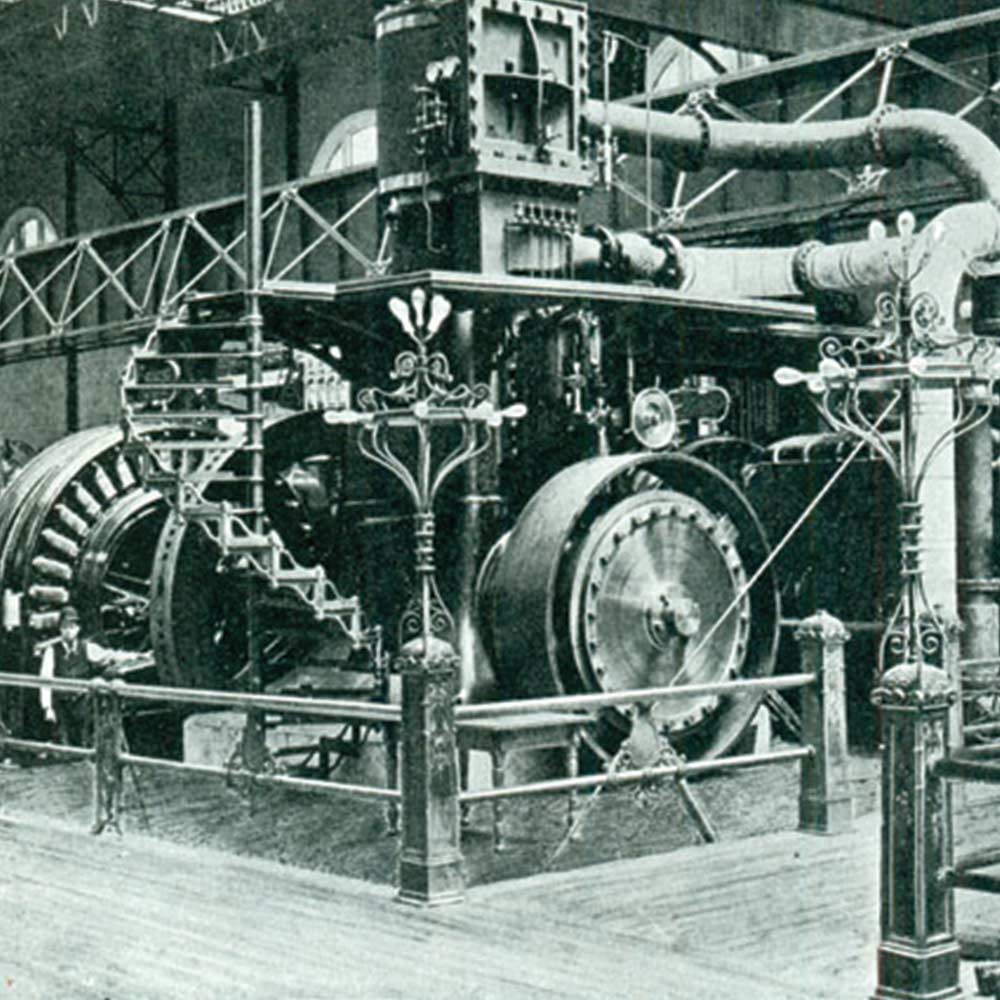

The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 was billed as an event that would be a glittering, monumental testament to the modern age. Organizers searched for a company that could successfully show the public that electricity was safe and part of the modern world. The Westinghouse Electric Company ultimately outbid Edison’s General Electric Company and was hired to illuminate the first fully electric-powered event of its kind in history.

On May 1, 1893, American president Grover Cleveland pushed the button that lit 100,000 incandescent lamps on the grounds of the Chicago World’s Fair. Between 27 and 28 million people—about 20% of the population of the United States—came to see the ‘City of Light’ that spring season. The event proved to the public that alternating current was not only safe, but a more efficient way to generate and distribute electricity. It remains the predominant current for large-scale power distribution to this day.

Comparing systems

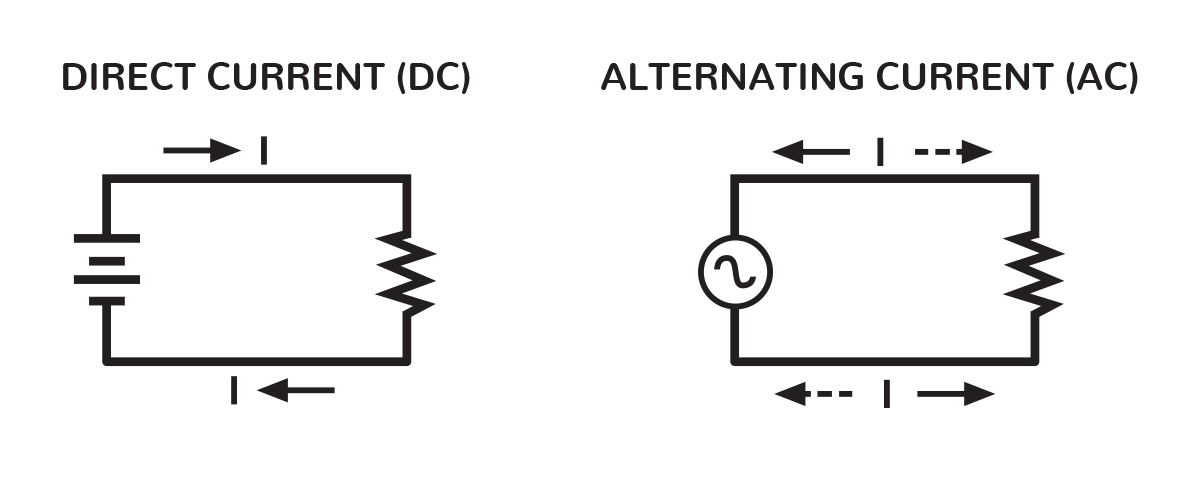

Direct current: Thomas Edison’s direct current system used the same level of voltage from powerhouse to end user. It required power stations to be built approximately every two kilometres, and massive amounts of copper were needed to transmit electricity. Given that electricity was mostly produced in urban areas at that time, Edison felt that these factors were not a problem for his direct current system.

Alternating current: Nikola Tesla’s alternating current system produced high voltage electricity at the power source and was transmitted to end users at much lower levels. Power lines and transformer stations were part of this system that could transmit electricity across longer distances.

Advantages of alternating current

- In the early days, alternating current electricity only required one generating station for thousands of kilometres of power distribution. With direct current electricity, a generator was required every 1.6 kilometres (one mile).

- Direct current electricity required two-thirds more copper to produce, making alternating current electricity more economical.

- Alternating current can be easily converted using a transformer to increase or decrease power voltage. The voltage of direct current power is fixed from powerhouse to end user and cannot be easily converted.

- During transmission, alternating current electricity loses less voltage than direct current electricity. Direct current electricity loses heat as it travels along power lines. Loss of heat leads to loss of voltage.

- Modern alternating current transformers are flexible enough to be installed anywhere, including atop utility poles and underground.